It’s 4:55 in the afternoon, do you know where your kid is? If you've got a challenging kiddo, they might have just jumped off the bus, ready to blast into the stratosphere, seemingly set to pick a fight (or throw a tantrum) as soon as you remind them to pick up their socks.

In these moments, it’s easy for parents and teachers to jump straight to problem solving. We want to quash the rebellion, as it were, and get back to business as usual as fast as quickly. Often that means we start throwing solutions at the problem to see what sticks, and our hastily assembled solutions are often of the “do this or else” variety. As in, “if you don’t put your clothes away, you can’t go get ice cream,” or “if you keep slamming your door, I’ll take it off its hinges.”

We call it Plan A - imposing our will in pursuit of our expectations. Convinced our kids are acting wantonly, we try to pull the lever of motivation, in hopes we can compel them to get their act together and get their dang socks out of the living room.

Unfortunately, we’re often surprised to find that our most emphatic, best-laid Plan As don’t always generate the outcomes we want. As often as not, Plan A actual pushes our already tuned-up kids farther into the wilderness, making things worse, not better.

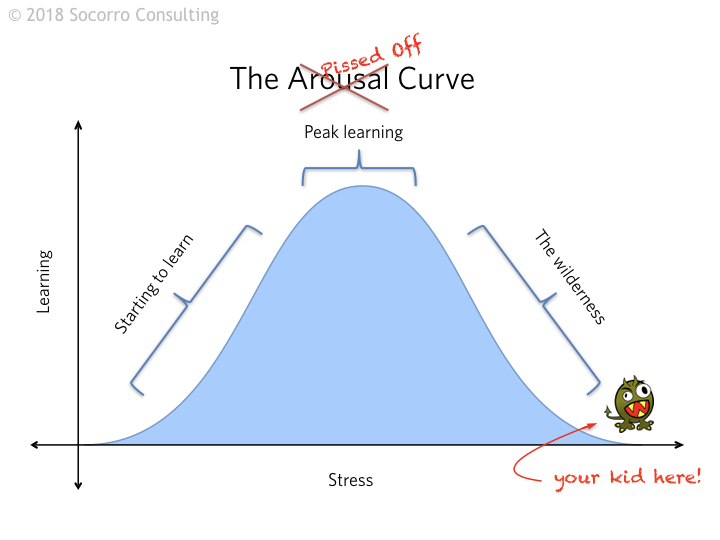

Time for two quick dips into neurobiology and emotional regulation. The picture above is what a clinician might call the arousal curve. One of my high school students renamed it the “pissed off curve,” and I like that name better, although “pissed off” can also be “angry,” “scared,” “worried,” and a whole host of other vexing emotions. The curve works this way: as you add more stress, you start climbing the curve. Some stress is good, even necessary for growth and development. Climb up the curve and you get to what we call “peak learning,” the sweet spot where you’re pushed out of your comfort zone and ready to take on new information. Keep adding stress, and you risk running past the peak learning zone and into the wilderness - lots of stress, no learning.

That’s dip one.

Your emoji brain.

Dip two is a brief exploration of the triune brain that you might just remember from the days of your psych 101 or human biology classes. If you don’t have a real life human brain to look at, you can actually approximate a model of a brain by turning your hand into a fist and bending at the wrist. See? Your very own model brain.

If you're looking at the image to the left, note that the thumb should actually be tucked in to the fist. That's what you get when you try to use an emoji to describe neurobiology.

Down by the wrist is the brain stem. It’s the part of your brain responsible for all the automatic functions - breathing, heart rate, fight or flight, etc.

The top of your hand is what we call the limbic system. The limbic system is responsible for our ability to relate to others.

The knuckles of your hand model of the brain represent the pre-frontal cortex, the promised land of the brain, and the part that’s responsible for the most complex and involved processes, namely, critical reasoning.

Our brains develop from back to front, from wrist to knuckles. You may know that our prefrontal cortex really rounds out its development around 25 or 26 years old, and that’s not a bad generalization. Although we retain the ability to change our brains throughout our lives, the malleability of the thing really falls off around our mid-twenties.

Now we’ve got our pissed off curve and our model of the brain. Let’s put them together.

Check out this video for the visual guide to this article!

Let’s go back to that curve - as you add more stress you get to peak learning. Add too much stress and you blast off into la la land. What does that mean in terms of our model brain? When we get really dysregulated, we actually start losing access to the more complex areas of our brains, the parts responsible for our critical reasoning - the knuckles on our hand model. We move from “what are my options to resolving this conflict in a socially acceptable way” to “crap, I’m in danger and I need to either beat the hell out of the danger or get away from the danger.” Fight or flight. Or freeze. Sometimes dysregulation looks like kids shutting down and dissociating from the stress. Don’t forget freezing.

What do you think happens to our ability to problem solve when we’re off in the boonies of our brain stem, which regulates our automatic functions that support our basic survival?

It gets real bad, man. That’s what happens.

Think about when we spend the most time lecturing our kids, though. A kid pops into the dean’s office and we start interrogating them about what they could do differently next time. Our daughter slams her door and we’re trying to explain why we don’t want her to slam doors. We’re nobly trying to communicate with the pre-frontal cortex, the knuckles, when it’s out to lunch and the brain stem, the wrist, is taking the messages and promptly losing them.

Trying to solve a problem when our kids are in their brain stems is an exercise in futility, but boy is that invitation to futility overwhelmingly compelling.

It's rough when kids blast off into the wilderness. They're lost in their brain stems at precisely the moment when adults usually want to bring the swift hammer of justice and critical reasoning down on their heads, rendering them effectively immune to learning much of anything, at least until they start back down the curve.

Thankfully, most kids can wind their way back down the curve when the momentary spike in stress eases. Thankfully, most kids have the skills to ride the peaks and valleys that come with the waves in the ocean of stress and anxiety they live in for much of their lives. Thankfully, most kids can work their way out of the woods on their own.

Most kids.

Some kids, maybe your kid, have a really hard time getting back from the wilderness. They get down in their brain stem, in the wrist of our hand model, and get stuck there. And while they're there it can be a lot to manage - you might get screaming, crying, dissociation, cutting, slamming, cursing, spitting or a combination of all of them or something else entirely (which is why we don't focus much on behavior at Socorro - it doesn't tell us that much about what's going on!).

So what, exactly, are we supposed to do with dysregulated kids who have gone off into the wilderness of their brain stems and can't find the way back?

Step 1: Regulate.

Remember where peak learning happens on our curve, and remember what happens to a kid's ability to learn when they're lost in their brain stems. It bottoms out, right? We'd be wasting our time trying to engage their pre-frontal cortex when it's closed for repairs. So our first order of business is to engage the kid where they're at, and that usually means we start by working with them and their brain stems.

Not sure where to start? Try your hand at one of these four types of regulation:

- Somatosensory - heavy work for the big muscle groups (think hugs, wall pushes, weighted blankets), rhythmic and repetitive activities (playing catch, rocking, drumming)

- Top down - reassurance. "You're not in trouble," "I'm not mad," "this doesn't seem like a big deal," "you're okay," etc.

- Relational - reflective listening, clarifying questions, practicing empathy (which means trying to understand what's going on for kiddo

- Disassociation - let it happen. Sometimes that's really okay, and the best thing for the kiddo.

There are all sorts of ways to regulate a kiddo, and your mileage with each strategy may vary. Something might work well one day and not the next. It's cool, it happens, keep trying, and when you get them back down to earth, it's time to remind them who you are.

Step 2: Relate.

Now that we’ve climbed our way out of the brain stem, we can get to work on the limbic system. This is where we focus on our love for the child, where we remind them of all the fun things we have planned, or the little things about them that we’re proud of. It’s where we explicitly realign ourselves with their interests so that they can feel we’re once again working toward the same goals. We're fighting the problem, not one another!

Focusing on our love, by the way, doesn’t just mean saying “I love you,” although that’s a cool place to start. My kiddo loves playing mancala and watching youtube videos together. Maybe your kiddo likes cards or hugs or playing catch. Whatever it is, do that!

Step 3: Reason.

Congratulations on your long walk out of the brain stem! You’ve covered a lot of ground, and now that we’ve got kiddo pretty well regulated and done the work to make sure they know we’re working together, we arrive back to the pre-frontal cortex where we actually stand a chance at solving the dang thing.

There are lots of ways to find solutions, but my favorite is Collaborative Problem Solving, an approach that has helped our family, and my work with kids in schools, tremendously. Collaborative Problem Solving is all about finding solutions to problems that work for everyone - adults and kids alike. It also happens to be supremely well-aligned with the neurobiology of getting a kid back from the wilderness that we just talked about.

If you’d like to learn more about Collaborative Problem Solving, check out this page, and if that piques your interest, know that we’re launching a brand new, 8-week session for parents dedicated to learning all about Collaborative Problem Solving this March, in Minneapolis.

Whatever way you use, use it with love, and remember there’s a pretty good chance that kiddo will slip back toward their wrists/brain stems while you’re going through the process. It’s tough work to think about a hard problem, listen to an adult’s concerns, and think about solutions and stay regulated!

The good. The bad. The conclusion.

I have some bad news: dysregulation is contagious. If your kid is blasting off into the wilderness and you join them there, you're both in trouble and are more likely to spiral off deeper into the woods than you are to make it back home.

But hey, I also have some good news: regulation is also contagious! A regulated person can regulate a dysregulated person, as long as they don't take the invitation to traipse into the woods themselves! And that's the crux of this work - kids get dysregulated a lot because they're still working on the basic skills they need to keep their business on lock.

By being a persistent, mindful regulating partner and politely declining the invitation to the wilderness, we can help them learn the skills they need, though. They can get there, and we can help, and that's pretty cool.

Stay regulated, y'all.

This article includes knowledge gleaned from Dr. Bruce Perry and Think:Kids, who have led the work in developing the concept of Regulate, Relate, Reason. More information about Dr. Bruce Perry can be found here. More information about Think:Kids can be found here.